BALCOMBE – THE SCHOOL OF SURVEY

1955 AT BALCOMBE

Introduction

We departed Kapooka on the 2 May 1955. Around 11PM we arrived at the School at Balcombe and were greeted by Captain Jim Stedman. Captain Stedman was to be our Senior Instructor on the 7/55 Basic Survey Course.

The School

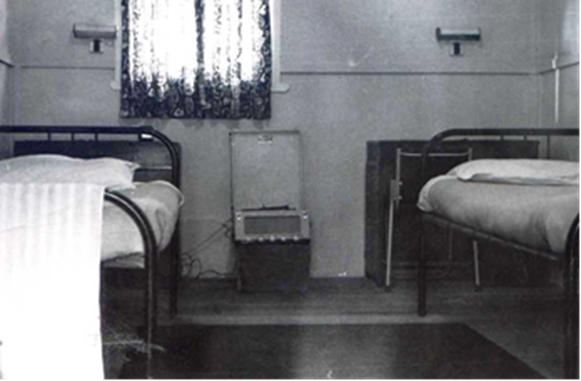

The buildings were of WW2 origin, corrugated iron clad in rows of about ten rooms with a covered concrete walk way along the front. It was two to a room. The floors were linoleum covered with a bedside mat (Mats Axminster, bedside) next to each bed, a table personnel for each occupant with desk and reading lamp, robes metal two door for the storage of our kit – this time we had our civilian clothes to hang and store; it seemed all very civilised. Directly opposite was the students dining room and kitchen – yes, we were referred to as students and not only that ‘Sapper’. I had come from being Private Skitch to Sapper Skitch, the rank name applied to all at soldiers at the ‘private’ rank level in the Corps of Engineers and because our heritage came from Engineers, to Survey. It was an oddly proud moment. My roommate throughout the course was to be John Etheredge, my roommate at Kapooka. This was not by request, purely coincidental. I was quite happy to be with John, a non-drinker and uncritical sort of bloke.

Balcombe Camp

Balcombe Camp : The Nepean Highway is at the bottom of the main aerial photo with the part occupied by the School of Survey in the enlarged inset. Mace oval is just off the highway and ‘The Briers’ south of the highway. The married quarters can be seen clustered north of the School. Port Phillip Bay and the Balcombe beach in the northern corner.

Barrack lines at the School of Survey

My shared room at Balcombe.

The School of Survey occupied a relatively small area within the quite large Balcombe military camp. Balcombe fronted the Nepean Highway that led south from Melbourne through numerous city bay side suburbs to Frankston (the electric train terminus) then to the town of Mornington and southwards close to the eastern side of the Bay through a number of bayside villages. Balcombe (a military camp and village), Mount Martha, Dromana, Rosebud, Rye, Sorrento and then Portsea on the extremity of the peninsula and the location then of the Officer Cadet School, the Australian Army’s second officer factory. In effect this beautiful peninsula was to be our training area, especially the area known as the Dromana Valley.

Entering the Balcombe Military Camp from the Nepean Highway one passed through three main school areas; the Army Apprentice School, scattered around Mace Oval mainly a RAEME establishment training young fellows from the age of 15 in mechanical and electrical trades and where they completed a civilian recognised apprenticeship; the School of Signals, on rising ground west of Mace Oval and then on the top of a low ridge, the School of Survey. West of the School of Survey was the army village of married quarters, Balcombe Village, and then down the slope and a winding road one came to Balcombe beach, a sand stretch fronting Port Phillip Bay. The Army Apprentice School was by far the largest establishment in the Balcombe camp and the School of Survey close to being the smallest. Smaller than Survey was the Army School of Music and it was somewhere within the Apprentice area, perhaps even part of it.

The School of Survey comprised a number of huts such as I have already described parallel to each other on both sides of the central road. As I remember it, on the southern side from the top of the hill leading downhill to the Apprentice School was the Sappers’ and Corporals’ dining room, two accommodation huts for Sappers and Corporals, an office hut where the CO/CI, SI and School Adjutant had their offices, then the small parade ground, the orderly room and below that a recreational hut. On the opposite side of the central road (it had a name) in about the same order was the fairly large kitchen where all meals were prepared, the Sergeant’s Mess, the Officer’s Mess and a number of accommodation huts the same as the one I have described. In one of those huts was a Q Store for all survey equipment. The area was neat and tidy, well maintained. The buildings were well painted, dark green with a cream trim. On the eastern side of the parade ground was a 60 foot Bilby Tower which we were to learn about later.

Training starts

Our first day at the School started with an administrative parade on the small gravelled parade ground in front of the orderly room taken by the School Sergeant Major, a warrant officer and the Adjutant, Captain Childs (ex British Army). I have forgotten the name of the SSM but he was a pleasant mild fellow. Some months later Warrant Officer Ken Shaw took over as SSM. It was purely an administrative parade and we soon departed for the class room. The 7/55 Basic Course had two components each of about 15 students. One group had commenced their course about two weeks before the second group and we in the second group were to catch up by working a six day week. For the first six weeks intending draughtsmen and surveyors were to be together undertaking the same initial training. More on that later.

From the parade ground we marched across to our class room and sat at about a dozen draughting tables, six down each side of the room, each with a stool. This was to be our home for the next ten months when we were not in the field. Captain Stedman was waiting for us and after a few minutes the SSM arrived with the Chief Instructor, the very avuncular Lieutenant Colonel Wally Relf. After welcoming us he handed us over to Captain Stedman who told us about the course; that we were greatly privileged to be selected to undertake the 7/55 Basic Course and laid down the ground rules in no uncertain terms – this course was costing the Army 2000 pounds per student and God help anyone who stuffed up. We were impressed. The course had started and with that, one of the great experiences of my life. Surveying, he said was one of the most ancient professions, practised by the ancient Phoenicians (or one other of those ancient civilisations) – in fact it was the second oldest profession in the world, leaving it to our imagination as to what the oldest was.

Puddles

Captain Stedman then introduced our course instructor who was to be our constant teacher and mentor for the entire course – Warrant Officer Class 2, ABM (Alec) Pond, known affectionately as Puddles.

For me Puddles proved to be an outstanding instructor. He was incredibly patient, had the knack of teaching and was such a thorough gentleman that none of us would dream of stuffing up or taking advantage of him in any way. He could certainly be firm and accepting of no nonsense and on those few occasions when someone might try him on, a few quiet words was all that was needed to sort that person out making him feel a dolt for even trying.

There were other instructors on our course, some who seemed to specialise in one thing or another, taking us for a particular subject or phase of our training. The course instructor of the first group was Warrant Officer Class 2, JW (Jim) Bounds, very different to our Puddles. WO2 Bounds was of a stern nature, somewhat humourless or appeared so. Nevertheless, his class responded well to him. I recall having him as an instructor on occasions and didn’t find his lessons particularly enjoyable. A question was likely to evince a reply you haven’t been listening lad with a mild punishment to follow – not quite take a dozen lines but similar in intent.

Basic surveying and equipment

Our course started with a few basic survey concepts. We were introduced to the theodolite at quite an early stage, setting up our instrument over spots on the parade ground. Each pair were allocated one instrument, that is, for our course component seven theodolites, all in excellent condition. They were quite old Vernier instruments, very much the same as the one I had used extensively in the Western Australian railways so for me the setting up procedure, centring it over a ground point, levelling it and reading the scales presented no problem. For most of my class colleagues it was a slow procedure. My partner during those early days was Johnny Williamson. Johnny was intending to move into the draughting stream once the course was reformed but that was some weeks off.

Then came the chain, a hundred yard long measuring band of steel, 1/8th inch wide and brass studded at each five yards. With each chain came the reader to allow distances to be read to a tenth of a foot. Again I was quite familiar with the surveyor’s measuring band – the chain – from my railway days but not the measuring techniques used by the Corps. With each chain a thermometer cased in an aluminium tube and a spring balance were issued, and of course two plumb bobs and an Abney level for measuring slopes. I had used the hand held Abney level before also in railway days. Measuring with a chain was to be at an accuracy of one part in 10,000. For each chain length a temperature reading was taken and a slope reading, generally to the head of the person at the other end of the chain. Then there was the actual chaining technique itself. For general chaining the practice adopted was called knee high chaining, that is, the ends of the chain were held knee high and plumbed over the mark with the plumb bob. Attached to the end of the chain was the spring balance used to pull the chain to a tension of 15 pounds. It was not an easy process and took some getting used to. All this had to be recorded in a chaining or traverse book and then each chain length reduced to the horizontal.

At the School in an adjacent paddock a traverse of about a dozen stations had been laid out, closing on itself and we all chained around this traverse keeping our distance from the pair ahead. There was of course a DS solution, that is, the distance between each traverse station was known by the Directing Staff (hence the term DS solution) so that our results could be checked and if too far out then rechained. With Puddles as our instructor there was never any pressure but that apparently was not always the case with WO2 Bounds.

Then came the theodolite and the angle read at each station between the two adjacent stations, face left and face right, two arcs with the initial setting first on zero degrees then 90 degrees. The Vernier scale could be read to a precision of 20 seconds of arc. An important part of angle observations was the plumbing of targets over the adjacent stations as well of course the plumbing of the instrument itself. The targets were the traditional red and white two inch square of paper inserted through a sharpened bush picket, the point of the picket being the plumbed point – the red and white being essentially for quick identification. We all used the same sharpened pickets, that is, we didn’t cut our own from the adjacent scrub, otherwise we would have soon denuded the scrub of all sapling timber. Finally, it was into the classroom to reduce the results by the process of latitudes and departures, a civilian survey term – in the army it was diff Eastings and diff Northings because all military survey was calculated or computed on a system of coordinates.

Computations

Traverse computations were taught in the classroom with lessons running parallel with the field observations. Because we in the second group were in a catch up mode we did a fair amount of this in the evening after dinner. We had to learn the use of seven figure logarithms and seven figure trigonometrical functions from Chambers Seven Figure Mathematical Tables, a very error prone process. The Corps provided computing forms which helped a great deal. Until one acquired a degree of dexterity with the use of the tables it could be a very laborious process. Calculating the diff Eastings and diff Northings around the traverse and applying them to the system of coordinates from station to station finally finishing up on the start point, in the perfect situation the final coordinates would be the same as the start coordinates, that is, zero misclose. If the misclose error was no greater than one part in 10,000 then that was very acceptable.

We learnt about error. There are three types of error, random errors which over time tend to cancel so long as all care is taken in observation – there are always some random errors; systematic errors which always accumulate and may be due to an instrument maladjustment and finally blunder, that is a single gross error. An unplumbed or knocked picket falls into the category of blunder. I found the final term vaguely amusing. At the end of this period of traverse measurement and computation it was becoming obvious that it was beyond the ability of some of our team.

Triangulation

From traversing we moved onto triangulation. In 1955 that was still the method of extending coordinate control over large distances and areas, largely overtaken in 1958 by the advent of electronic distance measurement. But the latter had not been even thought of in 1955. On the side of the Nepean Highway opposite the entrance to the Balcombe camp was a large paddock known to us as The Briers. There must have been a Briers homestead some distance away beyond the paddock but I was never aware of it. The School had set out a mini triangulation figure – a braced quadrilateral or maybe a centre point quad of five stations with a standard survey beacon over each. This is where we had our first taste of triangulation, observing the directions at each station, two students to a team. Johnny Williamson was my partner on this and I his. I observed and Johnny booked, then Johnny observed and I booked.

Landholders

I have often wondered at the relationship the School had developed with landholders throughout our training area, essentially that part of the Peninsula around Balcombe, Mount Martha, and Dromana, in fact the whole of the Dromana Valley as far west as Red Hill, Merricks and Tumbarumba. We all had unrestricted access to properties in order to carry out our observations, run traverses and do whatever we needed to do. Many of the properties were owned by very well known and wealthy individuals and one such place I remember was owned by Mr Brockhoff of Brockhoff biscuit fame. He was said to be something of a recluse, of German ancestry I think. Brockhoff’s homestead we knew as the Cupola because it had a cupola in its roof structure which we frequently intersected – rayed in – when we were conducting our surveying exercises.

Colonel Johnson (whom I never met)

All this had been set up soon after the School moved into the Balcombe camp then under Major Bert Eggeling, the WW2 Officer Commanding 5 Field Survey Company and later to become chief surveyor of the Snowy Mountains Scheme. Following Major Eggeling in 1950 was Major (soon after Lieutenant Colonel) HA Johnson. Many of the manuals with which we were to be issued were created by Colonel Johnson whose reputation and persona lived on in the Corps for many years. I have heard many impersonations of Colonel Johnson over the years. It seems he had many somewhat peculiar mannerisms and way of speaking. Nevertheless, it was he who made the School into what it was when I arrived in 1955. Looking back now it was a quite remarkable institution with a reputation that spread well beyond the Army. Colonel Johnson left the Corps in about 1954 after some sort of dispute, so it was said, and became Senior Surveyor in the Division of National Mapping in the Commonwealth Government, a position he held for quite a number of years. Enough of history for now.

Classroom

Although the field phase of training continued we also had days and evenings in the classroom learning the various computations used for reducing observations, calculating the sides of our Briers triangulation net and the broad theory of surveying. We started to learn about map projections and especially the Transverse Mercator projection on which Australian mapping was based. We learnt about the Australian Origin for all mapping, at that time the Sydney Observatory a location close to the harbour bridge and as old as Sydney itself. We learnt that the earth’s shape approximated an oblate spheroid, a mathematical figure on which all our computations were based. The spheroid had a major axis through the Equator and a minor axis through the poles; that the spheroid (known as Clarkes 1858 Spheroid) only approximated the true shape of the earth; that was the Geoid and at the point of origin the spheroid and the geoid were together. All this was pretty heady stuff. It was well explained in the Corps manuals. Of course all this was not in the first few weeks of the course but continued throughout the whole ten months.

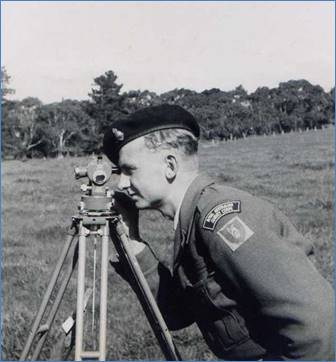

After the first couple of weeks on traversing and the Briars triangulation we moved onto the Plane Table. Plane Table rolled the years back somewhat. Even in 1955 the use of aerial photography had well and truly replaced the Plane Table for obtaining the topographic detail of a map – the roads, the buildings, the streams, land use and contours. Away went the chain and theodolite and out came the Plane Table board with the alidade and Indian clinometer. The Plane Table board measured 20 inches by 15 inches and was screwed to the top of a tripod that stood about waist high. I hesitate to describe the way in which the Plane Table was used and instead leave it to a few of my old photographs to give some indication. Plane Tabling incorporated graphically all the various techniques of topographical surveying that were in use at that time – traversing, intersections, resections, inclination.

Plain Tabling in the Dromana Valley

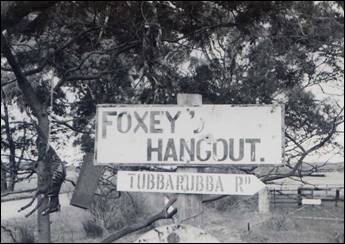

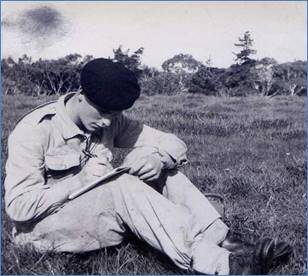

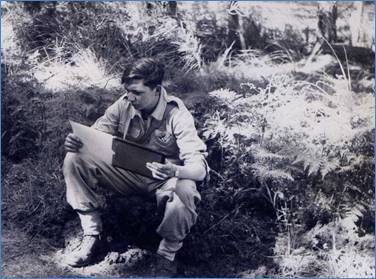

Our four weeks of Plane Tabling in the Dromana Valley would rate as one of the more pleasant experiences of my early army life. After Kapooka it represented a remarkable degree of freedom and individual responsibility. During those four weeks we traipsed around the beautiful Dromana valley following and sketching in contours, resecting to the surrounding trigs, visiting many of them to intersect points of detail in the valley (Mount Martha trig and Tumbarumba trig are in my memory), taking note of important features such as the cupola on the Brockoff home, Foxies Hangout on the road to Balnarring, that rather bizarre corner where dead foxes were hung from the branches of a tree as a warning to all foxes – you could smell it a mile away! And many others. We were doing all this in winter and some days were washed out by rain. On those days we stayed in the class room and inked up our Plane Table sheet. And so beneath our hand a real map started to take shape. For me it was a very exciting business but not for everyone. For some, Plane Tabling simply did not catch on; they couldn’t do it at all. Others made a late start, took them days to get underway despite much help from Puddles and other staff. The School had their DS solution and in the final analysis each of our sheets was compared with this. In fact, there was a great deal of tolerance in this and at one time Puddles admitted privately to one or two of us that it would take a year to become a competent Plane Tabler. These were the original topographers of the Corps in pre-war days.

Of course with such freedom of movement there were temptations along the way and for some that temptation was the Dromana pub. One or two were caught out quenching their thirst there resulting in a good dressing down. I don’t recall anyone on the course being put on a charge. On one occasion I was invited by a kind lady on a property to have a cup of tea and since the weather had closed in I did so on her veranda. It may have been Tumbarumba homestead. A hazard one had to avoid was the occasional bull. We were permitted to enter cow paddocks and generally found the creatures pleasant and friendly, quite inquisitive in fact. One could raise one’s eyes from the board where one might have been solving a small triangle of error to find a cow taking great interest in what one was doing.

The valley was quite a beautiful place with undulating green pastures, very attractive homes, winding lanes, patches of forest and gurgling streams. All of this was to appear on our Plane Table sheet. Finally, that phase of our training came to and end and we were declared caught up with the other part of the course. It was now time to separate into surveyors and draughtsmen.

PLANE TABLING in the Dromana Valley

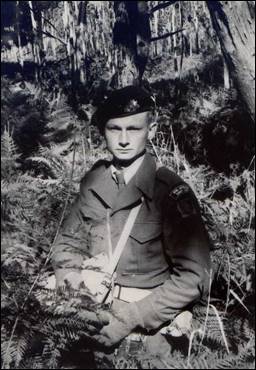

In the bush – it was cold; woollen gloves! With alidade & Indian clinometers

Plane Tabling In the field –Spr Skitch An interested on-looker

|

Max Howarth & Bob Thompson resect

AROUND THE VALLEY

Foxey’s Hangout on Tubbarubba Rd – a bizarre concept to discourage foxes. You could smell it half a mile away.

Merricks North Post Office Shady ways

Barometer traversing – John Lambie, George Ullinger, Steve Rose The chainman – Spr Skitch

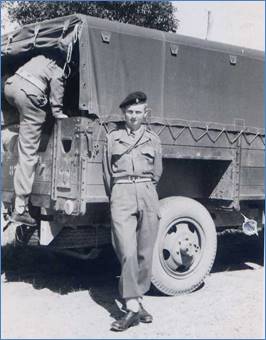

..............AND IN THE FIELD

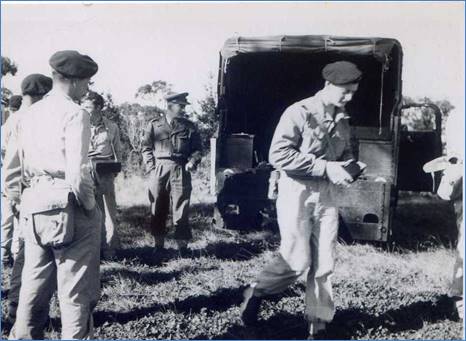

Early departure from Balcombe .......................................and arrival in the valley.

From left –Steve Rose, WO2 Alec Pond (Puddles), Bob Thompson

Spr Skitch using Kern DKM 1 theodolite John Van de Graaff using ????

Spr Gomm booking for me John Van de Graaff Pondering an air photo

Fellow students

At the end of the period of Plane Tabling and together with the other half of the course with whom we were deemed to have caught up we were split into two separate courses, still designated 7/55, the Draughting Course and the Surveying Course. I had no doubt that surveying was for me although it was suggested that I was suited to the Draughting Course. We went through an interview process being interviewed by Colonel Relf with Captain Stedman who had in front of them all our results so far. For me it was fairly perfunctory – I said surveying and that was accepted with a keep up the good work. That was certainly my intention.

My fellow students on the 7/55 Basic Survey Course are all shown in the photograph at the end of this article.

Surveyors in Training

Once we were separated into our two trade stream courses – both 7/55 – our detailed training in surveying continued in earnest. In the months leading up to Christmas 1955 we continued with intensive classroom activities, especially in spheroidal computations and computations on the Transverse Mercator Projection – addressing the problem of representing the curved surface of the earth on a flat sheet of paper. Puddles Pond had a remarkable skill in explaining these very complex concepts in the simplest of terms with clear quickly drawn diagrams on the black board. We studied geographical systems of reference, that is latitude and longitude with computations such as the conversion of Transverse Mercator coordinates to geographic coordinates – Latitude, Longitude and reverse Azimuth (bearing in lay terms), Simple Adjustment of trigonometrical networks and many others that I have long since forgotten. We knew little of the underlying mathematics of these computations. The Survey Corps had developed computation forms that took you from line to line down the page using of course the mathematical trigonometric tables – sines, cosines, tangents, secants cotangents – initially in logarithmic form and then moving to natural tables once we were issued with the Double Brunsviga calculating machine. Remarkably we were each issued with one of these very expensive calculators (we called them computers). The Double Bruns made traverse calculation very easy – enter the sine on one side and the cosine on the other, wind in the reduced distance and the diff Easting and diff Northing would come up in the display at the top – not electronic but purely mechanical.

A Double Brunsviga calculator

Field work continued around the paddocks of the Dromana Valley, more complete and extensive chain and theodolite traverses and theodolite observation of resections. In about September we put our Vernier theodolites away and were introduced to the microptic theodolite, the Wild T2 capable of direct reading to a single second of arc. With the T2 we observed the triangulation network around the Dromana Valley, three figures with a baseline on the floor of the valley and adjusted it using the simple adjustment procedure. We ventured into photogrammetry with principal point traverses, use of the parallax bar and were shown the mysteries of Multiplex plotting equipment – not to use but just to look at. We annotated photographs on foot wandering the Dromana Valley again with an envelope of aerial photographs and a pocket stereoscope. Back in the classroom we each had a Universal mirror stereoscope on our table and a couple of Old Delft magnifying stereoscopes for better defining small detail. On the photographs we identified pass points, principal points and control points which we coordinated in the field by resection and intersection. In the field we carried out barometer heighting each of us carrying a set of three precision aneroid barometers to a multitude of points we could identify on the air photo taking readings at each point and carefully recording these then checking in to the base barometer station at two hourly intervals located on a known height point. Reducing those readings to height differences and obtaining a height above sea level for each point visited. In the classroom again we contoured the air photos directly onto the photo image using our Universal mirror stereoscopes. Roads and tracks were classified according to width, surface and use. In effect we were making a map.

At a later stage we each produced a gridded compilation sheet on Kodatrace, a stable draughting medium, transferring the detail from our annotated and contoured air photos and using coloured inks to distinguish the detail – red for all cultural (man-made) detail, brown or black for contours, green for vegetation and blue for all water features. I don’t know that our compilation sheets could be classified as works of art; we were rather ham-fisted draughtsmen but the emphasis was on clarity of detail to allow the cartographic draughtsmen to create the final product.

Fortuna - for the first time

Towards the end of the year we had a two day excursion to Bendigo and the AHQ Cartographic Company. We bussed to Bendigo arriving mid-afternoon – I think we called somewhere else on the way, maybe the Map Depot at Kensington because we left quite early in the morning. Puddles Pond had told us what to expect – Fortuna Villa – once the home of gold mining magnate George Lansell and even some of the bizarre stories associated with the place. The Army had acquired it in 1942 for the wartime Corps expansion. We stepped out of the bus on a very grey afternoon and there it was, this huge old place with its turrets, verandas (mostly enclosed). It is hard to describe the impact that place had on me and the memory of it rests with me to this day. Fortuna was unbelievable. It seemed like something out of another place, anywhere but Australia. It was grey, unrelieved grey, half hidden by overgrown shrubbery. It was dilapidated; wrought iron from veranda balustrades missing (apparently taken and melted down for the war effort). There was something almost eerie about it. The lake – how did it get there? Was it a lake or a swamp? We were taken to our sleeping accommodation a hut (they called it the long hut) up a steep rise to a gravelled parade ground. There were a few tents down one side of the parade ground that we were told was national service accommodation but no national servicemen at that time. There were some old huts near the lake for what purpose was not clear. The kitchen and dining rooms were also at one end of the parade ground. That was where we were to eat. We were met by someone there; I can’t recall who but our own instructors seemed to be at home – all had served there at one time. We were told that the soldiers bar would be open and our time was our own. We were in battle dress with boots and gaiters and web belt – rather inappropriate for tramping through an old building. However, the following morning we fronted up to our first parade in the ballroom in hobnail boots on the once beautiful parquetry floor – it was raining outside. It was apparent that there was little respect for the old building – that was to come later. We toured through the various working and accommodation areas of the Villa. I observed the beautiful ceilings, especially in the music room, used as a draughting room and noticed the electric power conduits snaking diagonally across walls to power various instruments. We trooped through the tunnel under the building emerging under the coach house. The verandas were mostly enclosed with corrugated iron and roughly lined on the inside and used for file storage. The attic space at the top of the building was still being used for accommodation. At the back of the building was a long corrugated iron latrine block – at least a twenty seater – and a shower block. Such was Fortuna in 1955.

Fortuna Villa – late 1950s

Following our tour of inspection our bus took us back to Balcombe with the memory and impression of Fortuna lingering in my mind in subsequent years.

1956 BACK AT BALCOMBE

Sergeant Peter Constantine

The course started again soon after we had all arrived back from our Christmas leave, probably the following Monday. It didn’t take long for all of us to be well and truly back into it. Warrant Officer Puddles Pond continued as our course instructor with some others taking specific training items. Sergeant Peter Constantine taught us resections with the theodolite, setting up at a point in the Dromana Valley and observing a couple of rounds of angles (or directions) to three or more of the trig stations surrounding the valley and then calculating the coordinates of the observation point. There was a DS solution to the observation point against which to check our results. The solution involved assuming a set of coordinates scaled from the map and then calculating bearings and distances to the assumed position, plotting those on graph paper to form a triangle of error, resolving that triangle to give a more accurate position and then refining the process with a further calculation of position. It was a tedious process in the precomputer days using logarithmic tables – it was always assumed that you would not have a computer when out in the bush.

Peter, whom I got to know very well some years later, was a charismatic sort of fellow. Sometimes he could be very brusque and firm and at other times quite easy going, almost a larrikin tendency. The student who made any assumptions or took any liberties with Peter ran the risk of being cut down very coldly.

Astronomy

Captain Stedman started taking a more direct involvement in our course. We started looking at the sun and the stars. He introduced the course to field astronomy, initially through sun observations for azimuth (bearing) and then star observations for azimuth, latitude and longitude and all the associated computations. We were each issued with a Star Almanac for Land Surveyors and a Shortrede eight figure logarithmic trigonometric table for each second of arc, sines, cosines, tangents, cotangents, secants and cosecants. With this my interest in topographic and geodetic surveying reached a high point. I found an incredible fascination in establishing one’s position on the earth by angular observation to the heavenly bodies and over a period of weeks I learned the names of many stars and the constellations within which they fell. I bought my own copy of Norton’s Star Atlas and The Elements of Astronomy for Surveyors. The Corps’ own manuals of field astronomy were excellent. They were intensely hands-on practical. They guaranteed that you would get a result. The computation forms we used to arrive at a result in effect reduced the underlying spherical trigonometric formula to an easy to follow line by line process; four observations to a foolscap page. In the classroom from the blackboard we learned about solar and sidereal time; time by the sun and time by the stars. We learned about the Greenwich meridian and precise time signals, the time signal stations WWV, WWVH (USA) and JJY (Japan), how to tune into them on shortwave radio and how to set our stopwatches against the time signals and then time the stars as they crossed our meridian. Puddles, who was a very good draughtsman had the ability to draw very clear chalk diagrams on the blackboard of the celestial sphere on which all heavenly bodies were fixed; the celestial north and south poles, declination and right ascension, drawn in a way that truly looked three dimensional and clearly explained the relationship between these parameters.

We set up our Wild T2 theodolites on the parade ground in front of the orderly room. On the opposite side of the parade ground was the shortwave radio receiver tuned in to WWV and WWVH for time signals. We started with sun observations for azimuth – ex-meridian observations, meaning either side of the meridian, not on the meridian. With the sun one did not attempt to intersect the sun in the telescope (using a very dark glass over the telescope eye end) it is far too large, one simply places the cross wires against the left limb (edge) of the sun on face left then the right limb on face right and the mean becomes to centre of the sun. Star observations are to a pinpoint of light against a black background and hence more accurate. I was to become extensively involved in field astronomy in subsequent years soon after the course, a role I enjoyed considerably.

Final Field Exercise

And so the Course proceeded to its end on 7 April 1956. In the last couple of weeks, we undertook a field exercise when the Course, draughtsmen included, moved to a reserve at Balnarring on the eastern side of the Mornington Peninsula. We set up under canvass, a couple of army marquees and half a dozen 16’x16’ tents as well as a Willys field cooker. There we undertook to map from scratch an area about half the size of a 1:25,000 scale map area. The area fell into the overlap of about two 1:25,000 scale aerial photos so it was relatively easy to manage. A couple of control points could be established by intersection or resection but the rest had to be by chain and theodolite traverse. Barometric heighting was used for overall height control. Parties were assigned to traversing, field annotation, barometric heighting and every other field aspect. Other parties undertook the office work, contouring photos under Universal stereoscopes, transferring contours to compilation sheets and computing. After participating in field control aspects and sun observations I was assigned to computations with Joe Farrington. For meals a cook from the School kitchen did all our field cooking with one or two of us in rotation assigned each day to dixie bash. Cooking on a Willys cooker was by steam and was therefore salt-less and rather tasteless. But we had a good few steaks on a hot plate.

The weather held well and at the end of a fortnight (it may have been three weeks), we had two very credible compilation sheets on Kodatrace. It was then back to the comfort of the school.

On arriving back at the School we found that we had been moved into different accommodation on the opposite side of the road to make way for the 8/56 Basic Course and the interest of the instructional staff had been re-directed to the new course. We had some contact with the new chums who seemed to hold we 7/55 blokes in some awe. That was to change as soon as we hit the units to which we were to be posted.

Final exams, end of course and a posting

I am not sure whether we had had our final written exams before or after the field exercise. I think before and the papers were marked and other work assessed while we were on exercise. The whole of our course work was included in the assessment. The big day arrived and both the draughting and surveying students were assembled in the classroom. Lieutenant Colonel Relf was in attendance with Captain Stedman, Warrant Officers Pond, Bounds and Shaw. The course overall results were read out with the graded passes. Both George Gruszka and I achiever ‘B’ passes (the School had only ever awarded two ‘A’ passes) and I was dux of the course. Most others achieved ‘C’ passes with a few ‘E’ passes and one or two ‘F’s, that is fail. There was no ‘D’ in case that was mistaken for ‘distinction’. This system of pass classification was army wide and continued through all my 26 years of service. All passes earned the three star pay classification and the ‘F’s’ were given a further chance to qualify six or 12 months later by way of trade test.

Also on that day we were given our postings. We had previously been asked to indicate our choice of posting and I had said Brisbane – Northern Command Field Survey Section and that is where I was posted. Most of the others including all the draughtsmen to the Army Headquarters Cartographic Company, soon to become the AHQ Survey Regiment, the unit I was to come to know very well over the years that followed.

Our course photograph (below), was taken on the parade ground in front of the Bilby Tower.

Rear : Spr I.C. (Ike) Lever, Spr B.M. (Brian) Berkery, Spr J.L. (Johnny) Williamson, Spr J.R. (Joe) Farrington, Spr R.G. (Bob – Tommo) Thompson,

Spr J.G. (Jeff) Sweett, Spr A.P.C. (Tony) Slattery, Spr K.A. (Kevin) Moody, Spr R.H. (Bob) Beckett, Spr T.D. (David) King, Spr. S.A.(Steve) Rose,

Spr J.(John) Lambie, Spr G. (George) Ullinger.

Front : Spr W.P. (Spider) Webbe, Spr R.F. (Bob) Skitch, Spr S.G. Mehling, WO2 A.B.M. (Alec, Puddles) Pond, Sgt Cox, WO2 K.R.(Ken) Shaw,

WO2 J.W. (Jim) Bounds, Spr J. (Jerzy, George) Gruszka, Spr M.N.(Maurie) Jecks, Cpl S.A. (Sam) Chambers.

Absent : Spr J.J.(John) Van de Graaff, Spr I.G.(Ian) Etheredge (to clerical), Spr J.M. (John) Etheredge (to OCS later Psych Corps)

Original text and photographs by RF Bob Skitch (Lieutenant Colonel - Rtd), compiled, with additional material, by Paul Wise, 2017.